An Investigative Report by SahanPost

October 2025

Introduction

Sanaag, the second-largest region of Somalia, lies along the country’s northeastern frontier bordering the Red Sea. Long known for its rugged mountains and coastal riches, Sanaag is believed to be among the most resource-rich areas in Somalia, endowed with abundant marine, agricultural, and mineral resources.

Over the past decade, the region has witnessed a surge in artisanal gold mining. What began as small, local discoveries has now evolved into an unregulated gold rush — one that intertwines poverty, politics, and power, and increasingly attracts both local and international actors.

This investigation by SahanPost explores the gold reserves of Sanaag, the growing involvement of regional authorities and foreign interests, and the human and environmental consequences of this expanding extraction economy.

The Gold Belt of Sanaag

Sanaag is widely believed to hold Somalia’s largest deposits of gold, gypsum, salt, tin, iron, and even uranium. The Cal-Madow and Golis Mountains — stretching from the interior highlands to the Red Sea coast, form the heart of what many now call Somalia’s “new gold belt.”

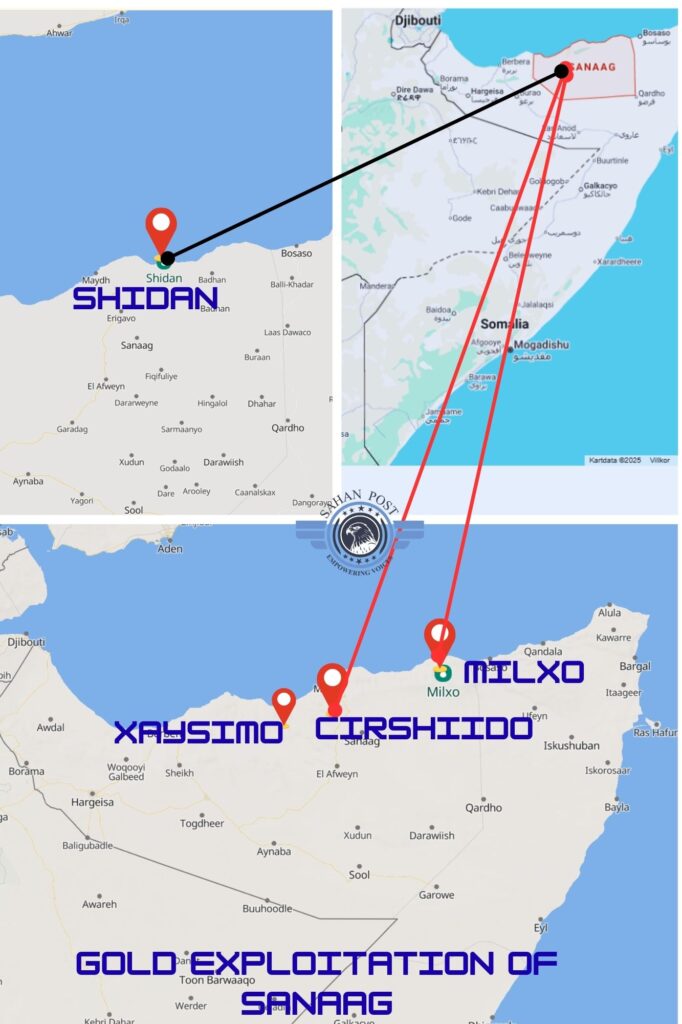

In 2016, residents of Shidan and Cirshiido discovered gold nuggets that sparked what became known as the Sanaag gold rush. With little equipment and almost no technical expertise, locals began mining using traditional methods. Within months, new settlements formed around gold-bearing areas as thousands arrived seeking fortune.

The main extraction sites, Milxo, Shidan, Cirshiima, Xaysimo, and Wadaagsan, now form a corridor of intense artisanal mining stretching across the mountains and coastal plains.

Conflict Beneath the Mountains

The discovery of gold in Sanaag has done more than boost the local economy, it has reignited long-standing clan rivalries, turning mining towns into flashpoints of violence. In 2019, tensions between the Noh Omar and Muse Ismail clans erupted into a violent clash in Shidan, a mining hub roughly 30 kilometers from Lasqoray District. The fight, driven by disputes over mining territories and control of resources, underscored the fragile balance of power in the region.

Eyewitnesses and reports suggest that Somaliland’s Marine Corps intervened in the conflict, reportedly aligning with one of the clans. Around the same time, authorities in Ceerigaabo arrested two key clan leaders from Shidan — Ibrahim Mohamed Hassan, known locally as Gacmayare, and Said Mohamud Said Bidaar.

The Shidan confrontation is a stark illustration of how, in the absence of formal regulation, mineral wealth can quickly become a flashpoint for instability, fueling both local tensions and broader insecurity.

Unregulated Mining and Environmental Ruin

Since 2016, Sanaag’s mining activities have expanded dramatically. Locals exploit both primary (lode) deposits,- such as orogenic and epithermal veins — and secondary (placer) deposits formed by erosion of gold-bearing ore.

However, the mining process has inflicted severe damage on the local environment. Hillsides are carved open, water tables are disturbed, and entire valleys have been reshaped by human hands. With no environmental oversight, these lands face irreversible degradation.

Most mining tools are locally made or improvised. The lack of training and safety standards has led to frequent accidents and enormous death, while deforestation and pollution continue unchecked.

Significant quantities of chemical waste are being discharged into the land, seeping into water sources and causing severe environmental degradation.

“Highly toxic chemicals are widely used in the production and processing of gold. Unfortunately, there is little regard for environmental protection, these substances are often dumped directly into the soil, leading to extensive land contamination,” said a local resident of Milxo Hassan Adan.

The Federal Government of Somalia currently exerts little or zero influence over the country’s mining sector. The primary legal framework governing mineral resources was Somalia’s Mining Law of 1984, supplemented by the Law on Natural Resources. In 2020, the Petroleum Law was introduced; however, no dedicated government bodies have been formally assigned to oversee or regulate the mining sector. As a result, the industry operates with minimal official oversight.

A Growing but Unequal Gold Economy

The price of gold has risen steadily- from USD 25 per gram in 2016 to around USD 80 per gram today, yet the wealth generated rarely benefits local communities.

In towns like Cirshiido, small local groups have taken it upon themselves to maintain order and regulate mining activities, albeit on a limited scale. Cirshiido, politically connected to former Somaliland President and local MP Abdikarim Meecaad, recently opened a gold processing facility, promising new employment opportunities for young people.

But just a few hundred kilometers away, Milxo, a small town with about 5000-7000 people, 60 kms to Lasqoray, Sanaag’s largest gold-producing site, operates entirely outside formal regulation. While official production figures are unavailable, sources told SahanPost that Milxo’s output could exceed USD 4-5 million per month. The site has earned a reputation as a “no man’s land,” attracting thousands of miners from across Somalia and even the neighbouring countries like Oromo people, of Ethiopia, some Chinese men, Indian and Pakistani as well as South Africans and Europeans were seen occasionally in Milxo..

“Every piece of land traditionally belongs to a specific clan, in Somalia, but Milxo belongs to everyone. No one enforces ownership, and it is being exploited by people from all over,” said local resident Said Ahmed.

The scramble for land has intensified as large companies move in, acquiring thousands of hectares and driving up prices. “The land is extremely expensive. In some areas, you may have to pay thousands of dollars just to obtain a small plot,” Ahmed added.

Despite its enormous output, Milxo lacks basic infrastructure. There are no healthcare services, no electricity, and no running water, making it one of the most expensive and precarious towns in the region. In this lawless gold rush, wealth and danger exist side by side, highlighting the perils of unregulated mineral exploitation.

New Revelations: The Foreign Connection

SahanPost has recently obtained documents indicating that the Puntland Government and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have conducted seismic and geological studies across parts of Sanaag, “Cal-Madow mountains“. The documents suggest an interest in assessing the scale of gold and other mineral reserves, and potentially securing future extraction rights.

According to the information reviewed by SahanPost, these studies appear linked to Dubai-based commercial interests seeking to expand their footprint in Somalia’s untapped mineral sector.

The survey proposal in question, titled “Survey Proposal for Euro Mark Group for Development Company LLC” , was prepared by the Australian-based company GeoResonance Pty Ltd. The plan covers more than 1,000 square kilometers across Somalia’s Puntland, particularly in the Calmadow area of the Sanaag region.

The document outlines an ambitious initiative to identify eight strategic minerals, gold, tin, lithium, copper, platinum, titanium, tantalite, and uranium, using what GeoResonance describes as “quantum-based remote sensing methods.” The proposal’s scale and technology claims have drawn attention for their boldness and the significant foreign interest it represents in the region’s mineral wealth.

Sources also revealed that several businessmen from Sanaag’s local clans have aligned with the Puntland administration to support the deployment of around 2000 security forces in mining zones and Calmadow, under the stated goal of maintaining peace and stability for the future productions of gold. For their safety, SahanPost has chosen not to disclose the names of these businessmen and Companies involved.

Meanwhile, Al-Shabaab maintains a limited but concerning presence in parts of Sanaag, particularly around Milxo. Individuals who spoke to SahanPost anonymously alleged that the group may have direct and indirect links to the local gold trade, raising fears that profits from mining could be financing militant activity.

The Route of Gold. From Mountains to Dubai

Most gold extracted in Sanaag is sold to local intermediaries who supply miners with equipment, fuel, or food in exchange for future deliveries of gold.

Gold from Cirshiido and western Sanaag is transported overland to Hargeisa and Berbera, where it is then shipped by air or sea to Dubai. Gold from Shidan and Milxo is routed through Bosaso, another key export hub, before reaching Dubai.

Once in Dubai, questions of origin, licensing, and ethical sourcing largely fade. The emirate’s gold market prioritizes low-cost supply, and according to investigations by The Times, has long served as a global entry point for African gold, including that sourced from conflict zones.

Sanaag’s gold rush has created new opportunities for wealth, but also deepened old divisions and invited new forms of exploitation. What began as a local search for prosperity has drawn in regional governments, foreign investors, and even militant actors, all competing for a share of the region’s mineral fortune.

Who Truly Benefiting From Sanaag´s Gold?

The absence of governance, environmental protection, and transparent regulation has left both people and land vulnerable. As evidence emerges of foreign-led geological surveys, Dubai-linked commercial interests, and growing regional militarization, the question remains: Who truly benefits from Sanaag’s gold?

Without urgent reforms, the region risks losing not only its resources but its stability, leaving behind a legacy of environmental destruction and social fragmentation.

© 2025 SahanPost Investigations

All rights reserved. This report may not be reproduced without permission.

Contact us: info@sahanpost.com

Discover more from SahanPost - English

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.